Gravitational Waves Reveal Most Massive Black Hole Merger Ever Detected

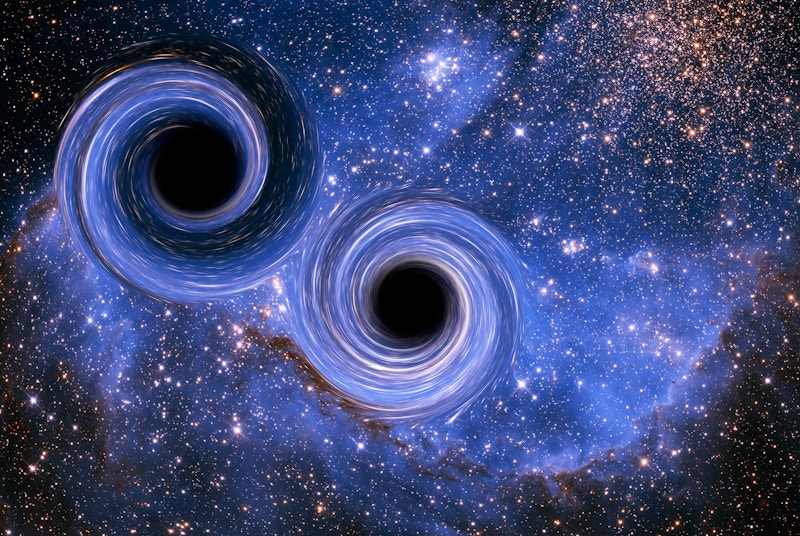

An international collaboration of scientists has detected the largest merger of two black holes ever measured, resulting in a monstrous black hole 225 times our sun’s mass.

While the combined black hole’s mass sets records, that’s not the only surprising aspect of the finding. The two original black holes seemingly had masses near or in a range largely forbidden by current astrophysical models — challenging assumptions scientists have made about how black holes form.

“No present theory has a completely satisfactory explanation of how to form such a system, but now that we know mergers like these occur, we can build out our understanding of stellar evolution and collapse to account for them,” says Will Farr, leader of the Gravitational Wave Astronomy group at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA).

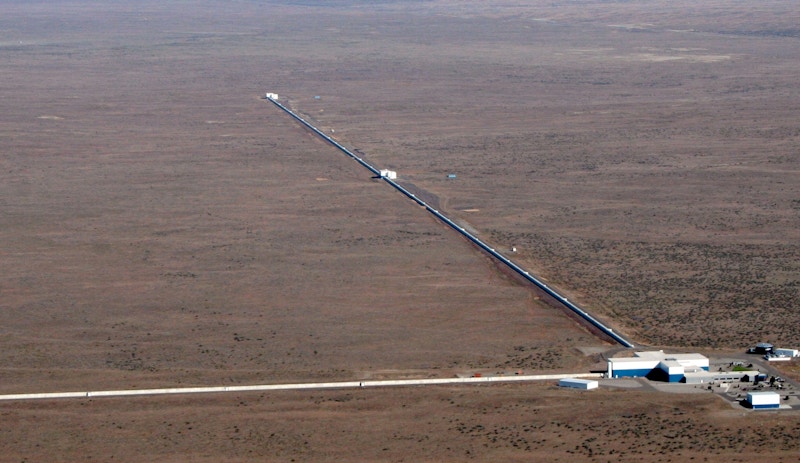

The detection was made by a collaboration of researchers from three experiments that measure ripples in the fabric of space-time created by events such as black hole mergers: LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA (LVK). The measurements of the new record-setting black hole merger were analyzed by Farr and other scientists at the CCA.

The researchers behind the discovery report their initial findings in a new preprint posted to arXiv.org.

A Split-Second Signal Details an Extraordinary Event

Gravitational waves are a key component of Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity and can provide critical insights into extreme cosmic events like exploding stars or merging black holes. Through the LVK collaboration, detectors stationed around the world (LIGO in the United States, Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan) measure gravitational waves by how they squeeze and stretch space. In 2015, LIGO became the first ever observatory to directly detect gravitational waves (also from a black hole merger), further solidifying Einstein’s theory and ushering in a new era of astronomy.

The 2015 detection pointed to a combined black hole approximately 62 times our sun’s mass. The LVK network’s new detection — captured in just 0.1 seconds and labeled ‘GW231123’ — suggests that two black holes collided an estimated 5 billion light-years from Earth.

The merger analysis suggests the two original black holes clocked in at roughly 137 and 103 times our sun’s mass. Though significant uncertainties are involved in those mass estimates, the results were surprising. That’s because there’s a theorized black hole ‘mass gap’ between 60 and 130 solar masses. Current theories of black hole formation say black holes within that range should be exceptionally rare.

“Black holes this massive are forbidden through standard stellar evolution models,” says Mark Hannam, head of the Gravity Exploration Institute at Cardiff University and a member of the LVK Collaboration.

The newfound merger suggests that there may be ways for such black holes to form other than through stars collapsing at the end of their lifespans. One leading possibility, the scientists note, is that the black holes may have gobbled up material through previous mergers.

The Ringdown Phase Mystery

CCA scientists played a leading role in analyzing and interpreting the gravitational wave measurements. Their results yielded more mysteries. They took a close look at the newborn black hole’s ‘ringdown phase,’ in which the black hole briefly wobbles as it settles into a stable state. This ringing doesn’t produce sound, but the gravitational wave data can be ‘sonified’ into tones. The tones coming from GW231123 raise more questions than they answer, says Farr.

“Each remnant black hole emits waves as discrete tones during this phase, and the combination of tones can, in principle, be used to characterize the properties of the spacetime near the black hole,” says Farr. “In this system, we see at least two separate tones emitted by the remnant as it is in this phase, but not in a pattern that corresponds straightforwardly to what we might expect for such systems.”

Another mystery comes from the new black hole’s motion: it’s spinning rapidly around its axis at a rate 4 million times that of Earth. The scientists suspect that this could also be a factor in why the black holes merged the way they did.

“There are signs that these black holes may have been rotating extremely fast in directions opposite to each other, leading them to precess as they came together like a pair of spinning tops,” causing their axes of rotation to wobble, says Maximiliano Isi, a CCA associate research scientist who worked on the analysis. “This potentially created a very distorted new black hole in the process that then wobbled as it settled down into a stable state.”

“We still have many questions about these types of signals, so we cannot say with full certainty yet what it all means, but to me all of these interwoven open questions, ranging from the behavior of dynamic space-time to the lives and deaths of stars, are extremely exciting,” Isi adds.

Frontier of the Unknown

The LVK collaboration will continue to improve its detection instruments and keep them running for long stretches of time to capture more black hole mergers, increasing the chances of catching more of these unusual cosmic events.

“As the detectors get more and more sensitive, and also observe for a longer time, we can see deeper into the universe,” says Farr. “Mergers like this are very rare, occurring only once per 100 million years in a galaxy like the Milky Way, so we need the detectors to have a high sensitivity and operate over the course of a year or more to have a good chance of seeing such a system.”

And when they do catch these signals, the researchers will keep trying to extract as much information as they can from them.

“At CCA, we’ve spent many years building an understanding of how it is possible for these very short signals to pack so much information about the black holes,” says Isi. “These signals appear for a very short time in our detectors and still aren’t fully understood theoretically, but we are making progress.”

There is also more to learn from the black hole’s tones, with more tones providing bigger clues and helping identify where current theories fall short and where new ones could be needed.

“Examining multiple tones is key for leveraging gravitational wave signals to infer the structure of the remnant black hole and to confirm if it matches what Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts,” says Harrison Siegel, a guest researcher at the CCA.

With many more mysteries to solve, the team is eager to continue their exploration.

“To me, this discovery highlights that gravitational wave astronomy is a discovery-driven field that is full of surprises, interesting puzzles and open questions,” says Isi. “We are at the frontier of the unknown.”

This article was updated on July 28, 2025, to correct the spin rate of the resulting black hole. The black hole was spinning at 4 million times Earth’s rotation rate, not 400,000 times.

Information for Press

For more information, please contact [email protected].