Bringing the Power of the Sun to Earth

Nuclear fusion reactors hold the promise of abundant, low-emission energy, but many obstacles remain before they will be viable for practical use. Since its inception in 2018, the Simons Collaboration on Hidden Symmetries and Fusion Energy has made significant strides toward improving a type of fusion reactor known as a stellarator.

There’s a power plant that can produce enough energy in 0.28 microseconds to meet the entire world’s electricity demands for a year. That power plant is 93 million kilometers away in the heart of the sun and operates as a giant fusion reactor.

Fusion occurs when the nuclei of atoms, such as hydrogen, merge to form a heavier nucleus, such as that of helium. In the process, a small amount of mass is converted into a huge amount of energy. This means a small amount of fuel can generate an enormous amount of energy. That energy can be turned into electricity if it’s used, for instance, to boil water to turn a turbine. Fusion energy has other benefits as well: It produces no direct carbon emissions and requires no special geography, and the fuel it uses, hydrogen, is abundant.

For over a century, scientists have dreamed of harnessing fusion reactions to generate abundant electricity. But maintaining the fusion reaction so that it generates more energy than it requires is a huge technological hurdle, leading to an old joke that practical fusion energy “has been 50 years away for 50 years.”

Designing a successful fusion reactor is beyond the reach of any one laboratory. It requires a deep understanding of the physics involved, complex mathematical considerations and cutting-edge computer science. In 2018, a group of researchers from across those disciplines came together to establish the Simons Collaboration on Hidden Symmetries and Fusion Energy with support from the Simons Foundation. Such Simons Collaborations bring together groups of outstanding scientists to address a topic of fundamental scientific importance.

The researchers behind the Simons Collaboration on Hidden Symmetries and Fusion Energy formed it with an ambitious goal: to design optimal nuclear fusion reactors that could bring the dream of fusion energy a giant step closer to reality. The team focused on designing a type of fusion reactor called a stellarator that has been notoriously challenging to develop. If the difficulties can be surmounted, however, a stellarator may overcome the challenge of stability — one of the biggest hurdles to bringing sustained fusion to Earth. The collaboration was able to come up with not just one successful design, but databases of them. One of these designs may become the first stellarator to produce net energy.

The collaboration “even exceeded my own expectations,” says Amitava Bhattacharjee, the collaboration’s founding director and a professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. “We were able to build community, which came to be known as the Hidden Symmetries and Fusion Energy team. This collaboration became the world’s largest theory and computational team dedicated to designing stellarator fusion reactors.”

Tokamak vs. Stellarator

The collaboration had a difficult problem. Designing nuclear fusion reactors is incredibly tricky due to the extreme conditions required to make fusion happen. For two atomic nuclei to fuse, they must overcome the mutual repulsion of their electrical charges. For the plasma at the center of the sun, fusion is facilitated by temperatures of 10 million degrees Celsius and pressures of trillions of pounds per square inch. In the lab, without the ability to match such extreme pressures, researchers need even higher temperatures to produce fusion — 100 million degrees. These high temperatures give the atomic nuclei enough kinetic energy to overcome their repulsion.

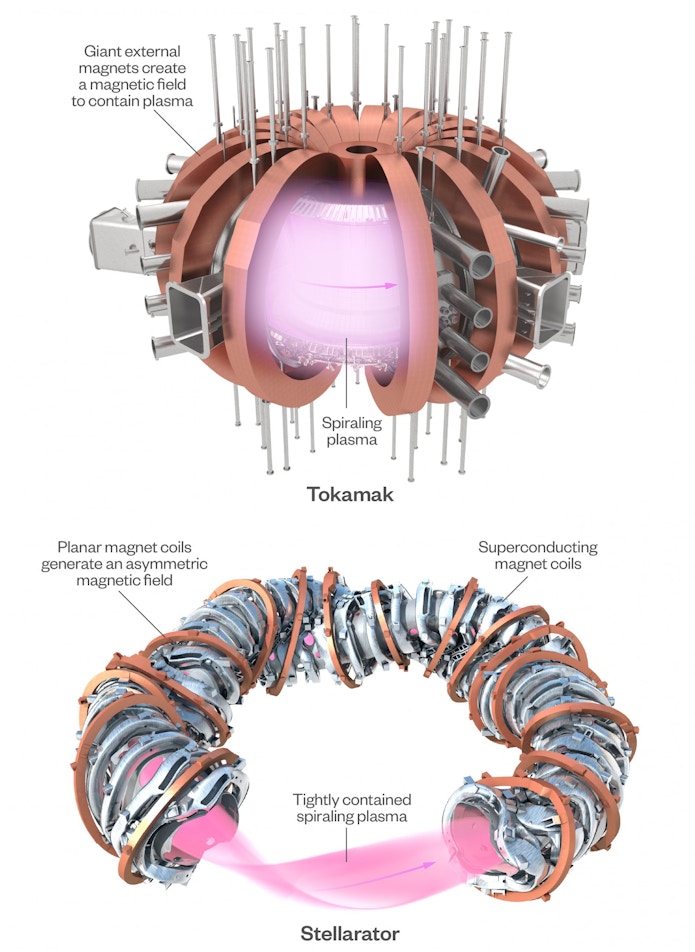

Plasma at such temperatures must be carefully contained. Reactors can’t just hold the plasma in a metal box, because if the plasma particles touched the walls, the plasma would quickly lose heat. Instead, reactors use powerful magnetic fields to keep the plasma in place. Charged particles follow magnetic field lines, which allows them to be confined away from the reactor walls.

One design for such a reactor is called a tokamak. Reminiscent of a doughnut (a shape called a toroid), tokamaks use giant external magnets to create a magnetic field. The charged particles of the plasma move along these magnetic field lines, forming a smaller, nested toroid inside the tokamak. In turn, this moving charge will generate another magnetic field, running perpendicular to the toroidal shape. The combined effect of both magnetic fields confines the plasma particles to spiraling paths on the surface of the interior plasma doughnut.

However, tokamaks have a stability issue. “The current is generating the magnetic field, but the magnetic field is the thing that’s holding the plasma and the current in place,” explains collaboration director David Bindel, a computer scientist and mathematician at Cornell University. “There is an opportunity for this feedback loop to develop. And that’s the real difficulty with the tokamak.”

A stellarator is a promising alternative. Instead of relying on an electrical current inside the plasma to create part of the magnetic field needed to confine the plasma particles, stellarators rely exclusively on external coils to generate a twisted magnetic field that confines the plasma to a spiraling shape. Coils of a stellarator are not planar, like in a tokamak, but twisted and warped (often shaped like the letter “D”). In a tokamak, symmetry allows for confinement. Stellarators instead rely on a ‘hidden symmetry,’ or quasisymmetry. This symmetry may not be immediately apparent from the outside, but the electrically charged particles in the plasma experience it as they interact with the magnetic field.

To understand this quasisymmetry, imagine that our twisted doughnut has ‘quills’ like a porcupine. Each quill has a length and a direction, which are given by the strength of the magnetic field at that spot. A tokamak’s quills are orderly, following a smooth, curving path around the surface of the doughnut. A stellarator’s quills, however, are different lengths, pointing every which way. However, if you follow certain curves on the surface of the twisted doughnut, each quill will have the same length, even if the direction changes. “It turns out that there’s this amazing property that, if you have certain special curves like that … it gives you good confinement,” says collaboration deputy director Matt Landreman, a plasma physicist at the University of Maryland.

The downside of stellarators? Due to their unusual shape, designing them is nontrivial. The equations optimizing the design of stellarators are exceedingly complex, to the point where it’s unclear whether they actually have solutions.

A burning question arose among researchers: Even if perfect quasisymmetry could not be achieved, would it still be possible to design a successful stellarator? With a team of some of the greatest minds in plasma physics, math and computer science, the Simons Collaboration on Hidden Symmetries and Fusion Energy prepared to find out.

The Art of Design

Collaboration members needed to tackle the complex geometry of the plasma inside a stellarator and the magnets holding the plasma in place. Changing the shape or orientation of a stellarator’s magnets even slightly can have a drastic effect on the shape of the plasma doughnut. In turn, changing the shape of the plasma doughnut affects how well the stellarator confines the plasma and how stable the system is overall.

The team sometimes focused its efforts on improving magnet design. At other times, they concentrated on determining the optimal shape of their plasma doughnut and then reverse engineering the shape of the magnets that could generate it.

“Optimization is a complicated art,” says Landreman. It’s a math-heavy field, and the mathematicians on the team brought a lot to the table. “Those of us in physics were kind of naive and knew a couple of the easy tricks but didn’t have a whole lot of experience with it. One of the things we really wanted to do with the collaboration was to get to know people in applied math, like David [Bindel], and learn about what are good methods for doing” optimization.

The mathematicians introduced the team to clever tricks for optimizing stellarator design. These methods allowed the team to see what would happen to their design if certain parameters were adjusted, and how adjustments made the design better or worse.

Finding an optimized magnetic field was the first step. “We want to get as close as possible to quasisymmetry,” says Georg Stadler, a mathematician at New York University and a founding principal investigator of the collaboration. “The second step is saying, OK, can we actually generate that magnetic field with electromagnets?” Even better was to optimize both the magnetic field and the magnets at the same time. “A main thing my group did was to propose to combine this into a single problem, and we were able to show some benefit from taking that perspective,” he says.

Working together, the team successfully streamlined the design process. Over time, they also became very successful at executing it. “We went from where working really, really hard, people could come up with a [single] plausible, optimized stellarator concept, to one where we’ve got databases of thousands and thousands of these things,” Bindel says.

Eventually, the team developed software called SIMSOPT that facilitates stellarator design. This code is now open-source and serves as a community resource for designing stellarators. “I think this mathematical tool, SIMSOPT, has completely revolutionized the field. It’s probably one of our biggest accomplishments,” says collaboration member Rogerio Jorge, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Having software to aid in developing stellarators helped the researchers solve one of the main questions in the field. Because of the complex geometry of stellarators, it was unknown whether it was possible to get close enough to perfect quasisymmetry, or if that was an unachievable ideal. In one of the collaboration’s key papers, Landreman and Columbia University physicist and collaboration member Elizabeth Paul demonstrated that quasisymmetry could be obtained at a precise level. “We could now start to think about scaling the stellarator to a fusion device, not just a concept … but actually [something used] for fusion,” says Paul.

A Common Language

Bringing together plasma physicists, mathematicians, engineers and computer scientists was necessary to overcome the obstacles to designing a stellarator. But those initial meetings weren’t without their own challenges. “Physicists and mathematicians have very different ways of explaining things,” says Paul.

“My memory of those [initial] meetings was, there were a lot of times one of the senior plasma physicists would say, ‘What we really care about is this technical detail,’” recalls Bindel. “One of the mathematicians in the room would respond with what was essentially a vocabulary question. [The physicist] would respond, and then another plasma physicist would jump in and say, ‘That’s absolutely wrong,’ and they would end up having an argument with each other. And the mathematicians were still completely confused.”

“Most of the time, we were just basically admitting every half hour, ‘Guys, we don’t understand you. This does not make any sense to us,’” says Stadler.

“It was clear that we needed a common language to communicate,” says Paul. This led to a necessary first step that turned out to be one of the collaboration’s biggest successes: establishing a common vocabulary. Collaboration members Lise-Marie Imbert-Gérard, Paul, and Adelle Wright worked on a dictionary to help their colleagues understand terms in fields different from their own. Eventually, the project developed into one of the key books in the field: An Introduction to Stellarators: From Magnetic Fields to Symmetries and Optimization.

The book begins with first principles — basic equations in electricity and magnetism, as well as the concept of charge — and moves on to optimization, stellarator design and open questions in the field. Not only was this dictionary instrumental in establishing a common language for the collaboration members, but it is now being used in graduate courses at multiple universities. “Building that common vocabulary has been one of the main themes throughout the collaboration,” says Landreman.

Supercharging Stellarator Research

Bringing everyone up to speed and maintaining a common vocabulary required regular communication to ensure that everyone was on the same page. So the collaboration hosted a plethora of meetings, both in person and online.

In-person meetings, from retreats to workshops to conferences, happened several times a year, and often this frequency was necessary. “Every three months there [were] a million other things people had done,” says collaboration member Alan Kaptanoglu, a physicist at New York University. “One of the good things about the Simons Collaboration is [that] it supercharged stellarator research.”

The collaboration also held online seminars every two weeks. These “Simons Hour Talks” often drew 30 to 45 people and covered everything from the behavior of the plasma inside a stellarator to new software, the design of coils, and future directions in stellarator construction.

They also held summer schools, which were standing room only. These summer schools helped bring everyone up to speed, especially early-career scientists and engineers. While the mornings were devoted to lectures, afternoons allowed attendees to focus on joint projects or meet other members of the collaboration. All in all, these meetings allowed computer scientists to learn about plasma physics, while physicists learned about mathematical techniques, and mathematicians learned how machine learning can aid in stellarator design.

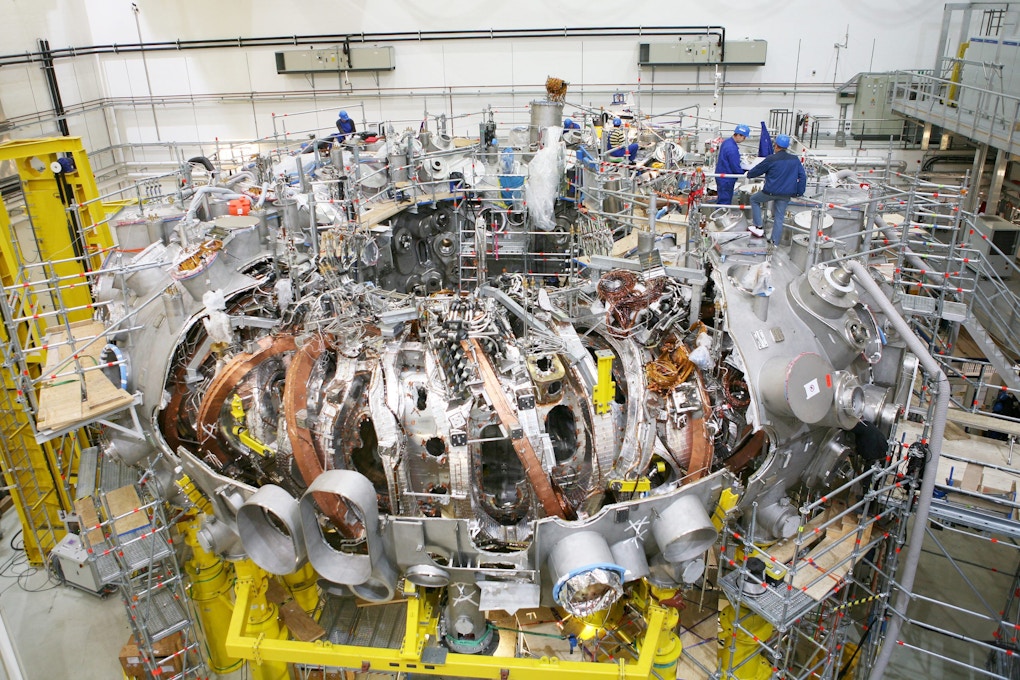

During some of these meetings, the team visited stellarators already in use, such as the experimental Wendelstein 7-X (W7-X) in Greifswald, Germany. Even though they worked on stellarators, seeing one in person was nothing short of inspirational.

“The stellarator was huge. It was amazing,” Jorge recalls. He says it looks like a bicycle tire, with a diameter of 11 meters but a thickness of only about 1 meter.

“I was very impressed, because it’s cool to see these monsters,” says Stadler.

Looking Back and Forward

Even as the funding from the Simons Foundation is coming to an end, the work they have accomplished has set the stage for exciting advances to come.

The collaboration’s efforts have indeed supercharged stellarator research. Many startup companies have emerged, some of which involve members of the collaboration. One such startup, Proxima Fusion, is using a stellarator design created by one of the graduate students in the collaboration. Electrons and Positrons in an Optimized Stellarator (EPOS) in Munich, Germany, and the Columbia Stellarator eXperiment (CSX) are also using the tools created by the collaboration in the design of their stellarators.

The Simons Foundation is also funding a group at Hampton University to build a tabletop stellarator based on one of the designs from the collaboration. It will perform experimental research to uncover the structure of the magnetic field and ways to divert particles that escape the field. Undergraduate researchers are heavily involved, supercharging their own careers. They “get a chance to see everything that goes into how you build a stellarator,” says Calvin Lowe, a professor of physics who leads the research group.

In addition to its achievements in science and engineering, the collaboration has launched the careers of many scientists, such as Paul, Kaptanoglu and Jorge. “The Simons Collaboration is one of the great things that happened in my career,” says Jorge. “I think it totally changed my path.”

Thanks to the work of the collaboration members, building a stellarator that can generate net energy may no longer be perpetually 50 years in the future. Future physicists and mathematicians will now have a far broader theoretical foundation. They have a library of stellarator designs at their fingertips and a better idea of what it takes to build a successful stellarator.

A net-positive stellarator will “happen in the next 10 to 12 years,” says Bhattacharjee. “Maybe I’ve had too much of the fusion Kool-Aid, but I have drunk the fusion Kool-Aid,” he adds, laughing.