A Stellar Revolution: How Open-Source Tool MESA Changed the Way We Study Stars

Since its creation by retired Silicon Valley software designer Bill Paxton, the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA) has illuminated the lives of stars and become a staple for stellar scientists. The Flatiron Institute’s increased support for the project marks a new chapter in the astrophysics tool’s storied history.

One of the most important contributions to the study of how stars evolve didn’t come from an astrophysicist. It came from a computer scientist. Bill Paxton earned a doctorate in computer science from Stanford University in 1977 and then made it big in Silicon Valley, joining the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center and later Adobe. While at Adobe in 1984, he co-created PostScript, the programming language powering the PDF file format.

“Thanks to Adobe, I was able to retire early,” Paxton said during a 2011 talk at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB).

After a decade of retirement in Colorado, Paxton got restless. Following a knee injury, he relocated to Santa Barbara. There, he picked up an unusual retirement hobby: graduate-level astrophysics.

Lars Bildsten, director of the Kavli Institute, recalls Paxton showing up on campus around 2000, backpack in tow, and asking to audit his graduate stellar structure and evolution course (lovingly dubbed “stars with Lars” by students). Despite not being a student, Paxton quickly demonstrated his dedication and extraordinary work ethic. “Unlike most people, Bill was doing the homework and even correcting the TAs,” says Bildsten.

In short order, Paxton completed all the graduate-level coursework required for earning a doctorate in physics, so Bildsten gave Paxton a research problem in stellar astrophysics: Predict how two stars interact as they revolve around each other. Paxton’s innate instinct for coding led him to turn this into a project to develop a modern computational approach to stellar evolution calculations. In 2004, Paxton published a tool called EZ, a model derived from astrophysicist Peter Eggleton’s code. But Paxton didn’t stop there. By 2005, he was developing something far more ambitious, something that would become a critical instrument for astrophysical research.

“I sort of cut my teeth on doing a reimplementation of Peter’s code and learned a lot,” Paxton said during the 2011 talk. “I took that, plus insights from any other code I could get my hands on.”

The resulting custom-built stellar evolution code achieved what very few other models could do without crashing — a simulation of the full life cycle of a sunlike star from its birth to its final stage. It accomplished this with reasonable accuracy and astonishing efficiency for its time. And it was the only model that could simulate a star’s evolution for a wide range of stellar masses. When Paxton told Bildsten his code simulated a several-billion-year evolutionary process in less than a day, all Bildsten could articulate was “Oh my.” That code became the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics, better known today as MESA.

“What I brought to MESA was the idea of a stellar evolution code the way I would like to see a piece of software designed,” Paxton said during the 2011 talk. “Let’s take advantage of where the hardware is now as opposed to where it was in the 1970s.”

In 2011, MESA was officially released to the public along with a ‘manifesto’ — an explicit set of principles for the intended use of the code. Bildsten explains that because MESA was never planned but instead evolved organically to become a community asset, that openness required obligations from its users. With the manifesto, Bildsten, Paxton and the other MESA developers, a team of expert volunteers supporting the instrument’s development from its conception, “made it clear we had a philosophy and rules we were asking the community to abide by,” Bildsten says. Stated within the manifesto are guidelines for using and contributing to MESA. For example, publications using the tool must properly cite it, any modifications or additions to the code need to be made publicly available, and users must help others learn MESA.

In the years since, MESA has become the gold standard for simulating the properties and evolution of stars. MESA’s open-source philosophy and rigorous documentation via peer-reviewed publications led to exponential adoption by the astrophysics community, with thousands of papers published using the software and more than 1,000 global users. In 2021, the American Astronomical Society recognized Paxton with the Beatrice M. Tinsley Prize — a biennial award for outstanding contributions to astrophysics.

Paxton died on July 23, 2025, but the incredible legacy he bestowed on the study of stars lives on. Bildsten notes, “With Bill’s passing, we have all lost a great scientist and supporter for early-career scientists. Bill not only cared deeply about getting it right but also shared his deep passion for clear thinking and deliberate language at all times. My research group meetings and the shared writings of MESA instrument papers were so much more exciting with Bill in the room, always challenging and encouraging all of us to do our best in our science and explanations. Simply put, Bill never left any stone unturned!”

Thanks to Paxton, MESA has revolutionized how researchers study the lives of stars, and with this revolution comes responsibility. When Paxton started stepping away from the project around 2020, the MESA developers had to keep it afloat, a tenuous arrangement for a cohort largely comprised of early-career scientists. After five years of unreliable funding and without Paxton providing full-time developmental support, the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) stepped in to provide MESA and its worldwide user base with security for sustained research, continued development, and community outreach and engagement.

“Scientific software is as fundamental to modern research as any physical instrument,” says astrophysicist Philip Mocz, who joined the CCA as a full-time software engineer supporting MESA. “MESA has revolutionized astrophysical research, and we are entering an exciting new era for modeling the stars to enable stellar discoveries.”

A Star Is Born

MESA was released with an ‘instrument paper’ — documentation of everything the code could do. Paxton once jokingly described the technical document as “just breathtakingly exciting reading,” but the state-of-the-art stellar evolution model’s reception by the astrophysics community was astounding.

“That is what gained community trust,” says Bildsten. “There was a stark cultural contrast because this was the first stellar evolution code that was intentionally written to be open-source and widely used.” That openness led Bildsten, astrophysicist Frank Timmes of Arizona State University and Paxton to create the MESA Summer Schools, which began in 2012 and continue to this day. These schools, which occurred on UCSB’s campus for a decade, created the MESA community of users and future developers.

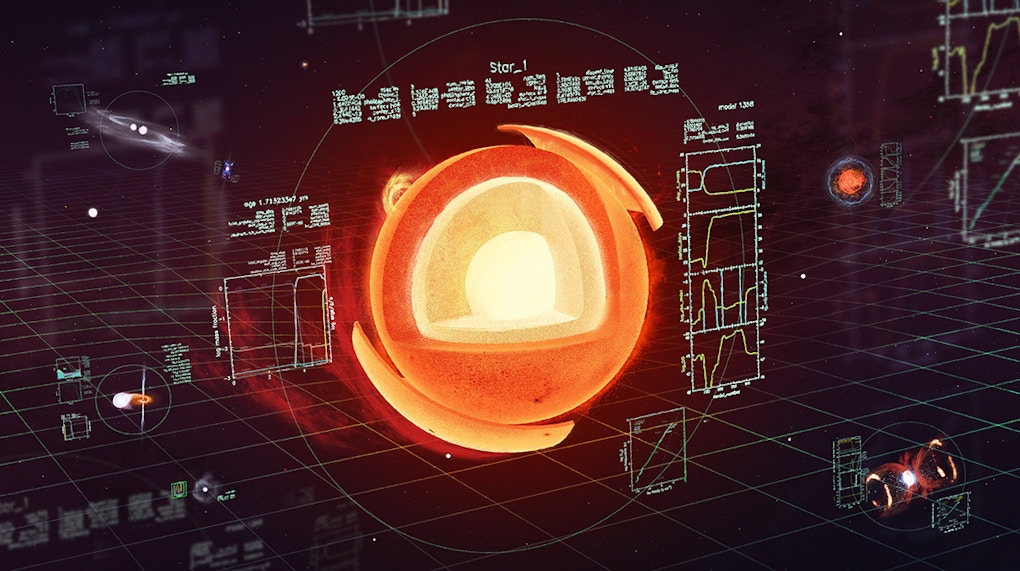

Astrophysicists use MESA to simulate how stars evolve from their initial formation to their final stages. Light from living and dying stars shapes how astronomers study the origin and expansion of the universe, along with the expected — and often unexpected — properties of the universe’s billions of trillions of stars and the astrophysical environments in which they reside.

Matteo Cantiello, a research scientist at the CCA who investigates the lives and deaths of massive stars, is a longtime MESA developer. He likens stars to atoms of our cosmological understanding and describes MESA as one of the most important tools for bridging theoretical models and observational data.

MESA’s rise to widespread adoption coincided with major advances in stellar observations that have opened new areas of science and revealed new properties of stars, such as previously unknown types of stellar explosions, internal rotation and earthquake-like waves that ripple through stars. Many of these findings have yet to be quantitatively resolved, and MESA provides a powerful tool for exploring these phenomena.

Part of MESA’s utility comes from its modular design, meaning that its components can function independently or in concert. This design, which includes stand-alone modules for binary stars, asteroseismology (the study of earthquake-like waves in stars), stellar turbulence and more, allows researchers to experiment with specific stellar phenomena in isolation or collectively.

“I always say, ‘The stars are right, and the theory is wrong,’ because we measure the oscillations of stars at such high precision nowadays that no theory is accurate enough to explain them,” says Conny Aerts, a pioneer of asteroseismology and an avid user of MESA. “When the observational data came flying in, literally, from space missions, MESA’s modularity and ability to couple seamlessly with the stellar pulsation code GYRE developed by astrophysicist Rich Townsend at the University of Wisconsin-Madison allowed my team to make major contributions to the internal rotation of stars. Meanwhile, our growing community started to deliver precise ages for the oldest stars and do archaeology of the Milky Way.”

Mathieu Renzo, an expert in the physics of massive stars, a MESA developer and a professor at the University of Arizona, adds, “This modularity is key because for a star, we only see the peel, like an orange. You need a code that allows you to swap pieces of physics and modify parameters to connect nuclear physics, stellar physics and gravitational waves that observations are revealing.”

And just as important as a star’s life is its death. The demise of massive stars creates phenomena ranging from all-consuming black holes to spectacular supernova explosions that generate enough energy to create all naturally occurring elements, including those critical for biological life.

“Essentially, most ingredients of life have been forged inside the hot and dense cores of massive stars that are released to the cosmos from supernovas,” says Cantiello, whose publication on some of the universe’s most massive and brilliant stars, called luminous blue variables, made the cover of the journal Nature. “We are literally made of stardust,” he says, referencing a quote by Carl Sagan.

Bridging Dimensions

MESA is designed to simulate stars’ life cycles, a process spanning from a few million to tens of billions of years. Simulating such a long process requires making approximations. Instead of considering every dimension of the star’s structure, MESA exploits the fact that stars are approximately spherically symmetric and only looks at the star’s radius, the distance from its core to the surface. This means MESA treats stars as one-dimensional objects.

“Because stars lead very long lives, one-dimensional models like MESA are needed to capture their full evolution,” Cantiello says. Adding more dimensions would make running a multibillion-year simulation impossible with current computational capabilities. Simplifying to 1D not only streamlines the simulations but also helps translate theory to predictions that can be compared to observations of real stars.

Understanding the complex dynamic processes of stellar interiors often necessitates calculations in three spatial dimensions. That’s because stars are not static. They rotate, producing turbulence and generating magnetic fields. Also, stars typically have companions, leading to interactions such as mergers that disturb the spherical symmetry implicit in 1D models.

“There is a constant interplay between fundamental theory, numerical models and observations.”

Matteo Cantiello

“If an observation of a star contradicts what we expect, we can zoom in and expand to 3D for a more comprehensive calculation, then take what we learned to adjust MESA,” says Cantiello. “This 1D-to-3D synergy is where we are heading at the CCA. We have computational resources, a comprehensive understanding of the theory, and we can use MESA to start laying the foundation of a pipeline.”

Coupling MESA to 3D codes can lend a greater understanding of the underlying physics, but any increase in MESA’s complexity must be reconciled with observations. “There is a constant interplay between fundamental theory, numerical models and observations,” says Cantiello.

MESA’s Impact

MESA’s robust yet flexible code has enabled significant discoveries.

Most recently, the dying red supergiant Betelgeuse, one of the sky’s brightest stars, made headlines. Researchers at the CCA, the University of Wyoming and the Konkoly Observatory at the HUN-REN Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences in Hungary investigated Betelgeuse’s two distinct periodic brightening and dimming cycles. A 2020 study using MESA showed that one of these cycles is a pulsation of the star itself, but the second oscillation remained an enigma.

In the new study, the researchers leveraged MESA to help discover that the unusual second oscillation is caused by a companion star (or “Betelbuddy,” as CCA Flatiron Research Fellow and MESA developer Jared Goldberg dubs it). During its orbit, the second star shifts the dust surrounding Betelgeuse, increasing or decreasing the amount of Betelgeuse’s starlight that reaches Earth. In a later study, MESA was used to calculate the final fate of this companion star, predicting that it will be swallowed up by Betelgeuse in the next 10,000 years.

The study of those earthquake-like waves within stars has enabled discoveries about how stars like our sun rotate internally. These discoveries provide information about the conditions in a star’s core and the astrophysical conditions present when the star was born. In 2022, researchers at the University of Innsbruck customized MESA to probe how the dynamics of baby stars shape the waves observed when they become adults, offering a more comprehensive understanding of stellar evolution.

And in 2024, a multi-institutional Nature study doubled the number of stars known to have consumed their planets, suggesting that at least 1 in 12 stars are planet eaters. Using powerful space telescopes and models, including MESA, the researchers studied twin stars and found differences in their chemistry and temperatures. These disparities were strong indicators of planetary ingestion, providing insights into the interactions between stars and their planets.

Perhaps MESA’s most impressive impact was the way it democratized stellar evolution modeling, galvanizing more generations of astrophysicists to gravitate toward the field. “MESA’s impact on the scientific community created a cultural change in the field, which is bigger than any individual discovery,” Renzo says.

“For me, it’s not about fancy discoveries of objects,” Aerts says. “It’s about finally having a tool that allows you to better learn stellar evolution theory, to improve it, and to validate or invalidate the theory.”

Engaging the Community

MESA is a powerful tool, and it takes a large community to maintain, develop and implement it. Easing the onboarding of new generations of MESA users is therefore critical to the project’s long-term success. “Learning how to use MESA is closer to learning how to play a piano than learning how to send a message with Twitter,” Paxton said during the 2011 talk. “There are tons of parameters, and learning how to use those effectively takes a bit of time.”

Recognizing this need for training, Paxton and the other MESA developers built an emphasis on education into MESA’s manifesto, as evidenced by the summer schools held each year. Recently, the CCA surveyed MESA users to “take the pulse of the community in terms of what features need to be preserved, and what new ones need to be implemented,” says Cantiello. Through this exercise, Cantiello and Mocz realized many were using MESA as an instrument for teaching.

“Teaching is embedded within MESA philosophy,” Renzo says. “The developers team supports MESA’s openness, its documentation, and strives to make the code not just user-friendly but student-friendly as well.”

University of Wyoming professor and MESA developer Meridith Joyce, an expert in computational astrophysics, a co-author and crucial contributor to the discovery of Betelgeuse’s “Betelbuddy,” and an ardent advocate for women in science, is taking the lead on MESA outreach and education. “The summer schools are arguably the most important product we have for community building and training,” she says, “and they are the first rung on the ladder to procuring new developers.”

The MESA developers have secured funding for the upcoming 2026 MESA summer school. And the CCA plans to devote resources to hackathons that will focus on implementing new features and resolving outstanding bugs.

MESA’s success has always been tied to such group efforts, predominantly from the team of developers, but also through contributions from the astrophysics community. “MESA users have revealed places where numerics or theory were lacking, and they have been the feedback loop that helped the community-oriented, open-sourced approach to really shine,” Cantiello says.

The Next Chapter

As the MESA community has grown, there has been an ongoing demand for a stable, guaranteed support structure. “What the CCA is doing is exactly that — an assurance of stability and novel developments,” says Aerts. The CCA is a perfect new home for the project, she says, because it has a deep commitment to making scientific software and data freely available to the scientific community to drive discoveries.

In a 2021 article published in UCSB’s news site The Current, Paxton explained what worried him about stepping away from full-time development. “I’m concerned about the health of the field in terms of finding a way not to rely on freaks like myself wandering in off the street who don’t need to have a salary, don’t care about tenure, and are just doing this stuff for fun and willing to spend huge amounts of time supporting other users.”

The traditional academic system rarely rewards the critical job of developing and maintaining software, and many projects end up dying out after a thesis is completed or the researcher responsible moves on to a new project. At the Flatiron Institute, such work is supported and celebrated.

In 2024, the CCA hired Mocz as a full-time software engineer dedicated to developing, maintaining and modernizing MESA’s code to help shepherd the project into a new era. Previously a computational physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Mocz has a background in numerical methods, high-performance software development, and simulations of nuclear fusion devices, which he says can be considered “miniature stars.”

“Bill Paxton paved the way for the project, and it has grown into something really big,” says Mocz. “I wanted to take the principles of modern software engineering and apply them in a collaborative, open-source setting. MESA is an incredible platform — it’s reshaped how we do stellar astrophysics — and I’m thrilled to help drive its evolution for the next generation.”

Joyce says, “As a team, we are ecstatic to have Philip. I love that I can tell my postdoc to focus on the science rather than the maintenance.”

Speaking about Adobe’s PostScript programming language, Paxton said, “It was great until we had customers.” Now, MESA has many customers but doesn’t have Paxton, hence the need for a new generation to take the reins. “When Bill decided to step down, development declined significantly because there was nobody with the freedom to devote the tremendous amount of time and work necessary to maintain a model of this scope,” Bildsten says. “There is no place else like the CCA, and the investment in Mocz means MESA has a new home and is well set up to succeed.”

Bildsten is confident that the values on which MESA was founded are safe and that it is time to let the next generation of astrophysicists lead the way. “Bill is the reason MESA exists,” he says. “This is simply the next phase of the project led by a different set of people with different goals but with the same philosophy.”